What is neurodiversity, and why will we continue to hear more about it in our industry?

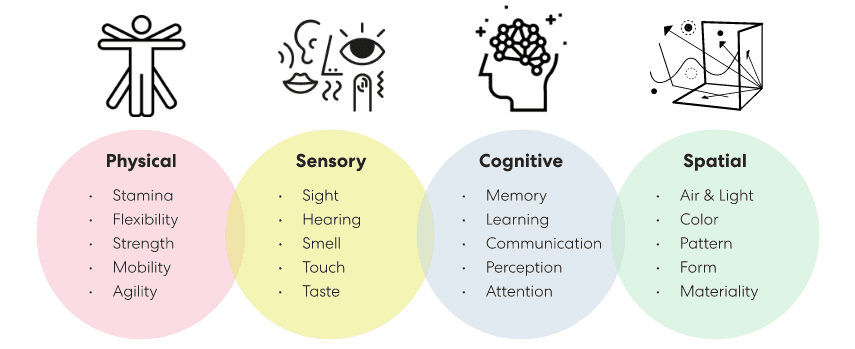

Judy Singer, Australian sociologist, coined the term Neurodiversity in 1999.1 Neurodiversity describes the different ways our brains are wired, leading to unique skills, needs, and abilities. Individual differences shape social dynamics, cognitive functioning, motor skills, attention, sensory stimulations, speech, language, and learning. Like biodiversity, the term neurodiversity does not intentionally define a certain subgroup of individuals, but rather speaks to the infinite variations of the way people think.

In contrast, there is a movement utilizing the term neurodiversity to empower select subgroups with diagnoses. The term has evolved to classify individuals as either neurodivergent or neurotypical, with neurotypical referencing those who display “average” patterns of thought and behavior. The broader terms begs the question, what defines “average” or determines who is considered neurodivergent?

Currently, the answer is dependent on individual perspectives, with all reflecting a range of subgroups when referring to neurodiversity. For example, an aggregated view defines neurodiverse as those with Autism, Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder, Down Syndrome, Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Dyspraxia, Dysgraphia, Meares-Irlen Syndrome, Hyperlexia, Tourette Syndrome, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Synesthesia, Trauma Disorders, and other mental health conditions.

The list is extensive and often expanding. The answer varies based on how one defines ‘normal’ or neurotypical. Furthermore, within each diagnosis there is a range of classifications (or intensity) and differing needs making designing for individuals based on diagnoses limiting or restrictive. Additionally, medical diagnosis omits those unable to or have yet to receive a diagnosis.

On the other hand, diagnosis resulting in “labels” can also empower. For some individuals with neurological needs, labeling their condition provides a sense of belonging, and more importantly, relief. Currently, labels impact benefits, the welfare system or social support mechanisms, and who receives assistance. For employees, a label can provide support by providing a term to reference when requesting accommodations.

So, as designers, how do we support diagnoses without being constrained by them?

Balancing the benefits of a diagnosis with the limitations it can entail demands that we be aware of diagnoses, appreciate the various methodologies to support them, but not restrict our design considerations to specific labels. Instead, our design parameters need to focus on flexible solutions to benefit everyone, to empower each person with options to support their needs. Thus, we return to Judy Singer’s original intent of the word neurodiversity, the different ways our brains are wired.

Biodiversity vitalizes our ecosystem just as neurodiversity vitalizes society. When everyone thinks the same, we might as well clone ourselves. We would experience the same problems and rarely develop innovative responses. Diversity in the way we think, and our range of cognitive abilities leads to better problem solving and more creative solutions.

Neurodiversity, as originally intended, acknowledges that “normal“ is a gray area. Focusing on labels of diagnoses is limiting. Furthermore, individuals comprise layers of physiological and psychological needs that vary from person to person, as explored by comorbidity. But if spaces can adapt to any employee’s need, organizations can optimize work for more of the community while advancing both the health of their community and business.

So, why is neurodiversity becoming such a prevalent topic within our industry? Because we, as designers, have a special opportunity to shape the spaces that influence the quality of life, for individuals, and community. Professionally, we have a responsibility to understand the range of needs individuals require to thrive. By creating environments that respect and accommodate equity, diversity, and inclusivity, we break down barriers while building a holistic approach that leads to innovation and productivity, regardless of individual needs or labels.

1 Doyle N. (2020). Neurodiversity at work: a biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. British medical bulletin, 135(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ld...