As architects and designers, I believe that we have mastered the power to make use of our creative skills in extraordinary ways. From hours of designing to years of learning, we possess the ability to create magical moments across interior and exterior spaces. It wasn’t until a few months ago, under the guise of a “zoomed” world during a global pandemic, that I truly began to think one step further — to the capabilities of virtual space.

Employing an architectural firm to design a virtual space is quite unheard of in the gallery world (or really, most worlds for that matter.) We worked to design a digital gallery for the debut exhibition of Minoru Onoda: Through another Lens, which was directed by Anne Mosseri-Marlio.

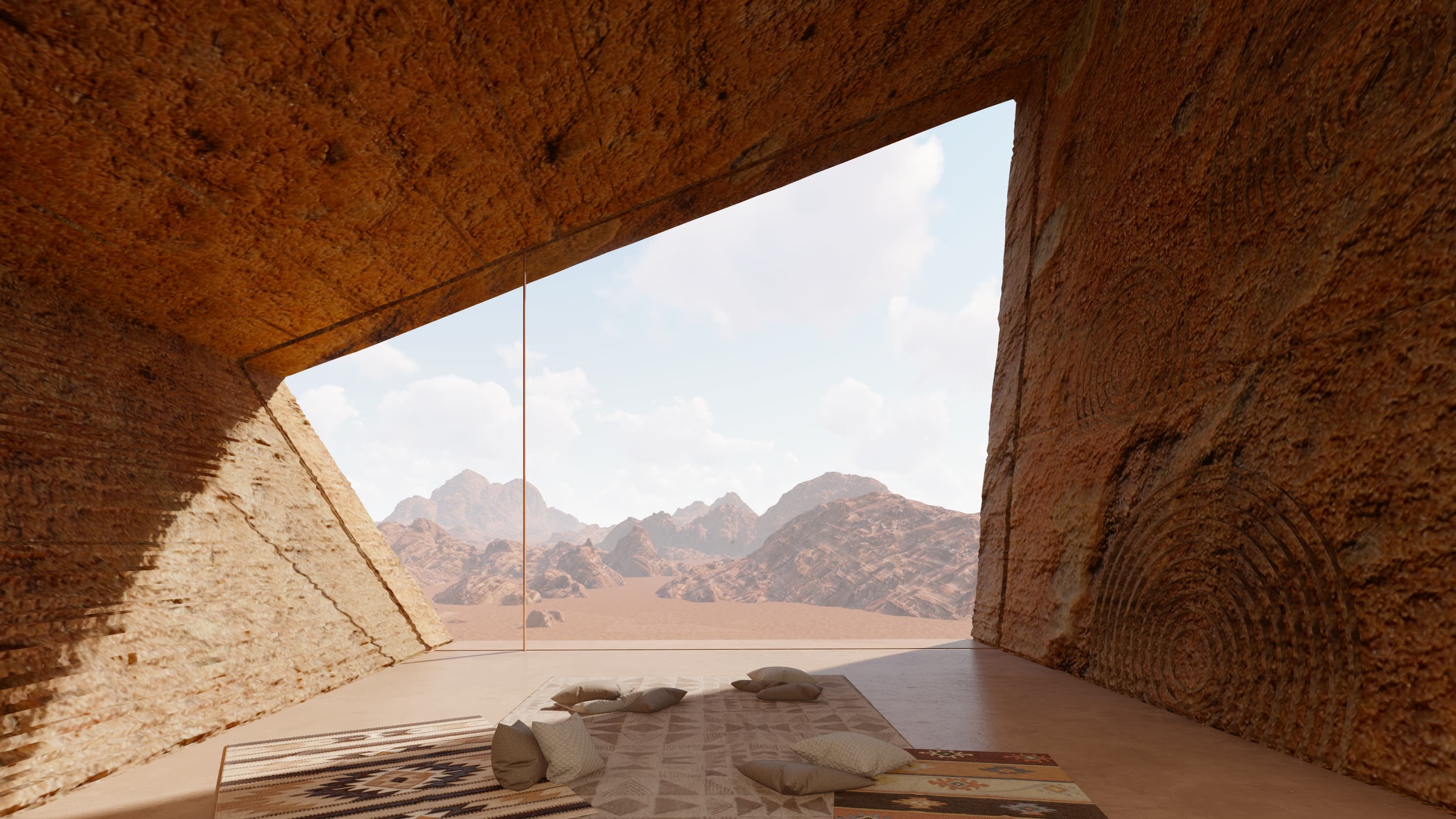

With most “OVRs,” or online viewing rooms, depicting two-dimensional art, we ensured that the virtual gallery incorporated heightened realism. We partnered with The Boundary, an architectural visualization agency, in a quest to develop an immersive, simulated space that could meet the demands of an expanding online art market.

Our studio seeks to encourage design to be more accessible across a wider audience. In every project, whether it’s a private home or urban development, we aim to identify ways in which we can closely connect with clients and the future inhabitants of the space.

With this in mind, we noticed an occurrence that was amplified by the global pandemic—many artists and curators made the transition to online platforms with the hope of displaying their artwork to the public, as there were very few opportunities to do so in physical space.

We viewed this particular project as a chance to authentically share breathtaking art and architecture, while minimizing the gap between simulated reality and our physical existence. The intention behind the virtual gallery went beyond restrictions brought on by the pandemic—our focus was accessibility for all.

In our conversations with the gallery’s director, we contemplated ways to make the space more meaningful. Creating transportive interior spaces is onechallenge. However, developing these spaces, I believe that designers should ask themselves this: how can we make this feel as interactive, immersive and inclusive as possible?

We utilized our experience in the brick-and-mortar sector to develop a lifelike viewing experience—visitors are genuinely transported to another zone.

Considering the standard features of an online gallery, and our mission to incorporate accessible elements, we looked to form the space with meticulous attention to detail and realism—from the floor to the ceiling, and the size to scale. The gallery bears an essence of freedom unlike any other.

The online space is physically accessible to anyone and everyone with an internet connection. When it came down to design, we opted to incorporate inclusive elements, such as a ramp. We wanted to amplify representation—certain components helped make it accessible to those who may be intimidated by the gallery world, live a great distance from the city, or generally don’t have the means to visit these spaces.

Virtual reality is an exciting tool within the architectural world, and we’re just scratching the surface of technological possibilities. In my eyes, there are a number of applications for this type of interactive, immersive technology—many of which we are actively working to uncover.

All images courtesy of Oppenheim Architecture, by The Boundary